Uncle Jim, 1942

In my earliest memories of Jim Ida, my great-uncle, he was already an old man. I remember him as a slender man with gray hair and wire-rimmed glasses, soft-spoken with a gentle smile and a slight stoop in his shoulders, which I assume was from his years working at a desk for Lockheed. Married to my grandmother’s younger sister Sada, he and his family came down to Salinas from Palo Alto for Thanksgiving and my grandmother’s annual summer barbecue, where his main responsibility was mixing drinks—even now, years after his passing, everyone still talks when we get together about how smooth and perfect his martinis were. Like most children with their extended family, I never really got to know Uncle Jim all that well, though I remember him congratulating me when I got into a top-tier engineering school for college. But I always liked him. I’m pretty sure everyone did.

The photograph above was taken in 1942 by the great photographer Dorothea Lange, who had been commissioned by the War Relocation Authority to document the removal of the 110,000 Americans of Japanese descent from their homes in the Pacific coastal regions, and their incarceration in government camps in the interior. Before this photograph, and another from the same day, I’d never seen Uncle Jim as a young man or a child before. In 1942, in this photograph, he was 17 years old.

As far as I know, my family—like most Japanese American families—doesn’t have any photographs from their time in the camps or the removal beforehand. This is unsurprising, because cameras were not allowed in the camps. The images most of us have seen, if we’ve seen any, come from WRA photographs like Lange’s, or perhaps from Ansel Adams’s famous photographs of Manzanar. We all have stories, of course. But actual photographs are rare. I first saw the above photo when I was in my late thirties.

In the moment this photograph was made, Jim and his family were on their way to the Tanforan Assembly Center, where they would be detained until later being sent on to an incarceration camp in Topaz, Utah. Tanforan is now a mall but at the time it was a racetrack. Some families were kept in hastily built barracks, while others slept in horse stalls. In Salinas, where my grandmother’s family lived (and lives), it was a similar story, with families first being sent to a temporary detention center in the Rodeo Grounds and then to a larger camp in Poston, Arizona.

I look at this photograph and I see the uncertainty and worry in Jim’s body language. The tilt of his left foot, the ankle rolled following the angle of his body as he looks off out of the frame. The way that I’d thought at first that he was holding his right fist in his left hand, but that on looking closer I see the little crook of his left pinky, how his fingertips brush along the knuckles of his other hand in just the same way I sometimes do when I need to ground myself. He doesn’t know what’s going to happen but he knows it’s not good.

At 17, Jim was not my uncle yet but he was a citizen of the United States, having been born here. So, too, were my grandmother and her siblings, and even her parents. My grandmother’s father was in the first graduating class of Salinas High School. On the other side of her family, her uncle Harry played semipro baseball—I’m told that a photo of him is part of the collection at the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. Their citizenship did not protect them from being rounded up, labeled as enemy aliens, and incarcerated in the desert far from the only homes they’d ever known.

A common refrain in activist parts of social media is “our institutions will not save us.” As we look ahead toward an administration that promises to inflict great harm on many of the most vulnerable people in this country, there are still many people who believe that they will be safe because of their citizenship, or because they see themselves as fine, upstanding, hard-working members of their communities. The people in my family had committed no crimes when they were ordered to report for detention with only the belongings they could carry with them, nor indeed had the tens of thousands of other Japanese Americans who went to the camps with them. Citizenship, civil rights, character, and even innocence mean nothing in the face of a government and a country that is determined to hate and fear you.

As was true for many Japanese American families, my family lost a lot due to the incarceration. The Japanese on the West Coast had come as cheap immigrant labor in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but by the time immigration from Japan was shut down in 1924, my family and many others had begun to prosper. The immigrant generation were not able to own property themselves, but through their American-born children they began to farm for themselves, own small businesses—barbershops or grocery stores or boarding houses. Most of that was lost during the incarceration, with Japanese-owned businesses shuttered and Japanese homes and land sold off at deep discounts, mostly to the white people who called for their removal in the first place. Still, what my own family experienced was not as terrible as what many others faced at that time in other communities or countries—to the best of my knowledge, none of my family members died in the camps, and all of them eventually returned home, or made new homes elsewhere. It could have been worse. It was bad enough.

Still, though every Japanese American family I know has stories of camp, of hardship, of losing their property and their dignity, many of them also have stories of people who helped them. People who took in their pets or stored belongings that couldn’t be brought to the camps, who looked after their homes or offered them work when they returned. In Monterey, a group of more than 400 community members signed a petition urging kindness and welcome to the returning Japanese American families. Of course, this petition only came about because of an organized effort to prevent the Japanese from returning to the Monterey Bay area. But it still mattered.

This is what I’m thinking about as we brace for what is to come. Things will break down. People will be uprooted and endangered. And though there will be protests and actions, and these may help, it will not be enough to save everyone from what’s coming. It may not be enough to save anyone. But the attempt still matters. As do the small acts of care that we can offer, one to another.

Over the course of my life, I’ve shared my family’s story of incarceration many times, to many different people. Sometimes people are shocked that such a thing could happen in America. Sometimes people are surprised that this episode of our history isn’t often taught in schools. For me, this has never been history. It has always been alive. I have never been able to talk about the Internment without becoming emotional, because even though it didn’t happen to me, it happened to people I know. Uncle Jim passed some time ago now, as have many of my family members from his generation, including both of my dad’s parents. But Auntie Sada, Jim’s wife, is still with us, still comes to Thanksgiving at the house that used to be her sister’s, where my aunt and uncle live now.

Why do I share this story so often? Why am I sharing it now? In part I’m sharing it because, as happened back in 2017, I see so many people declaring that they will fight, resist, stop the coming atrocities. And I am, of course, glad of this. It’s necessary to fight. But I wonder what will happen for people if and when the fight fails, and the atrocities cannot be stopped. How do we continue after hope fades? For me, the ability to offer care, comfort, respite to those in danger comes much less from hope than from love.

I’m reminded of a quotation from the Senegalese conservationist Baba Dioum, one that I was first introduced to when I worked a summer job at the Monterey Bay Aquarium: “In the end, we will save only what we love, we will love only what we understand, and we will understand only what we have been taught.” This story is a small thing I can share with you so that you might learn something about where we’ve been and where we’re going. To get you to consider who you love and how to turn toward that love, how to widen it and deepen it, so that you can offer care to those who need it. There will be so much need, so soon.

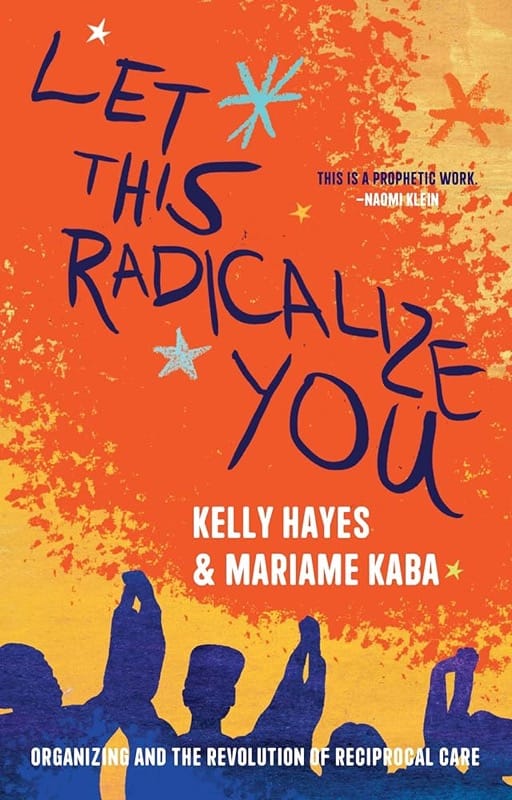

November 2024 Featured Read: Let This Radicalize You, by Kelly Hayes and Mariame Kaba

In the wake of the 2016 election, a lot of people—including me—found themselves newly awakened to the necessity of becoming politically active, of getting organized, but without the connections or experience to know exactly what that looked like. Looking around at social media and my in-person friends and acquaintances today, I’m seeing a lot of the same energy now, and a lot of the same confusion about what organizing looks like. Back in 2016, those of us who became new activists and organizers did eventually figure some things out on our own about what works and what doesn’t, but the most valuable lessons we learned mostly came from the people who had already been here doing the work. That’s exactly what this book is.

The title comes from a quotation by Mariame Kaba, one that often gets shared around social media after some new atrocity emerges: “Let this radicalize you instead of leading you into despair.” Kaba and co-author Kelly Hayes are experienced organizers, well-known for their work in prison abolition, and in this book they’re sharing a lot of hard-won lessons from their own work.

I think whether you are new to activism and organizing or are returning after a break, there is a lot of useful and practical information here. It’s not a “how-to,” exactly. Rather, Hayes and Kaba show you how organizing works in the day-to-day, show you how an organizer thinks, show you how activism isn’t about individual heroism but instead that it’s something anyone can do when we prioritize interdependence and connection. They show you how hope isn’t a feeling but rather a practice, and how “good” isn’t something you can be but rather something that you make in the world. This book won’t give you the answers to every question you might have about organizing but it is a great place to start.

Here are some purchase links:

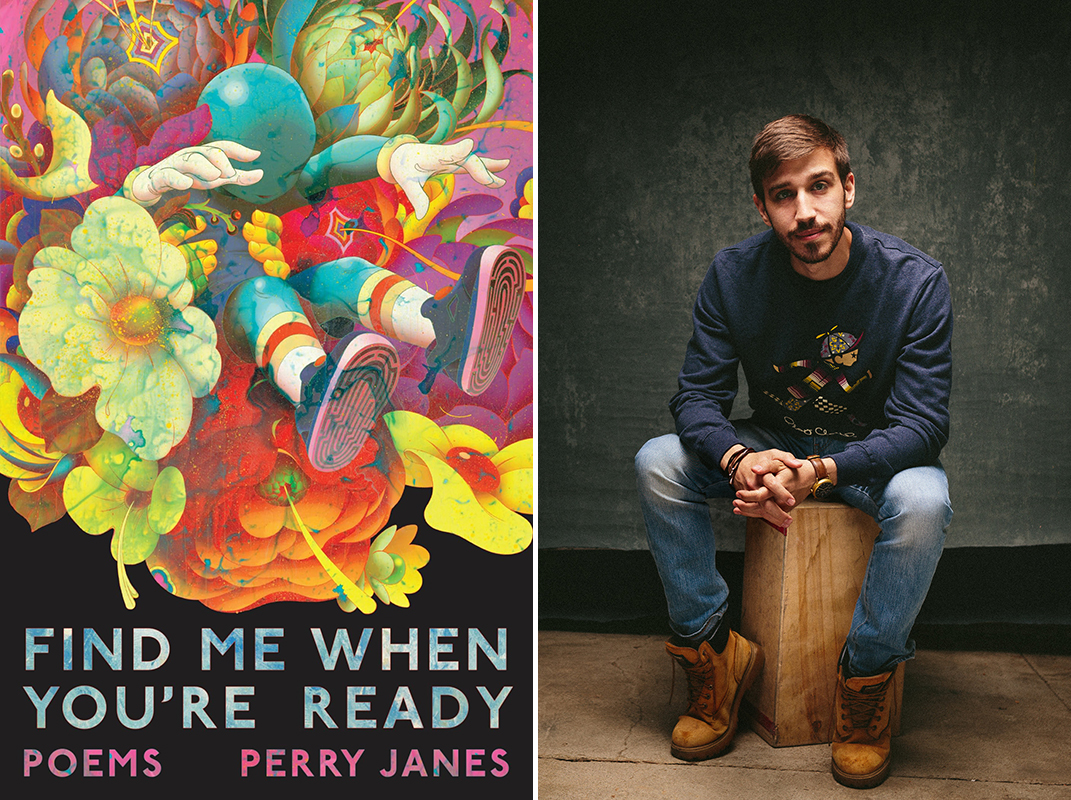

New KTCO: Perry Janes

The thing that struck me the most when reading Perry Janes’s debut poetry collection, Find Me When You’re Ready, is not that it contains poems about trauma. Rather, it’s that the poems about the speaker’s trauma make up such a relatively small part of the collection. The rest of the collection doesn’t ignore what came before, but rather than dwelling in the moment of trauma, the later poems allow the speaker to move on and begin to heal. That’s just one of the things that Perry and I talked about in our conversation, which I hope you enjoy.

Hey, It's Me: Some Interest and Also Some Trepidation

If there is any person who has been a part of this show without having actually appeared in it, it’s David Naimon. Back in episode 7, Rachel said she feels like “we’re in a throuple on this podcast with David” and then asked if we should finally invite him to join us. Well, we did, and this is it.

We start off in a very Between the Covers-ish kind of space, discussing form and genre in podcasting and how that all applies to the making of Hey, It’s Me. But by the end, we wind up in an extremely Hey, It’s Me place. After all, wild tonal shifts are what this show is all about.

Hey, It's Me: There's Always Going to Be a Disconnect

In today’s episode, Rachel and I are talking about in this one is neurodivergence, the stigma around mental health diagnoses, asking for what we need, and having to hold other people’s feelings.

It’s an interesting thing, making a show where there is such a gap between recording and release. Every episode becomes a bit of a time capsule. There is almost always something one or both of us has changed our minds about since we recorded, or that we no longer feel. Or, as in this case the situations in our personal lives or in the world at large have changed.

We recorded this episode in August. The election hadn’t happened yet at that point, obviously, but it was also still relatively early in Rachel’s son’s cancer treatment. We aren’t the same people we were at that point, and our lives don’t look the same—in some small ways, in some big ways.

We have recorded a conversation about the election, so you know. That will be released at the end of December. It’s possible by then that the things we say in that episode won’t be relevant anymore, or won’t represent how we think or feel anymore. But that’s okay. This show has always been more about the process than the end result. As we’ve said: we don’t know what we’re doing, but we’re doing our best.